Guest blogger Emily Danchuk is an intellectual property attorney and founder of Copyright Collaborative, which is designed to educate, empower and unionize artists in the fight against copyright theft.

Part One: Onboarding with Anthropologie, West Elm and the Devil

In recent years, companies like Anthropologie, West Elm and Crate & Barrel have begun collaborating with artists and designers, realizing that the negative consequences of (and press from) wholesale infringement outweigh the benefits in our politically-correct world today.

When a consumer breezes through the furniture, clothing and homewares sections of these companies’ catalogs, they can now see pages dedicated to genuine collaboration with artists, with write-ups about the artists and touchy-feely love for the creators of original designs. Everyone is happy and making money, right? We’re all onboard, now that the Gods are working with the artists they used to steal from. Right? Well, let’s step back.

Recently, I was hired to review some Anthropologie vendor agreements for a client. It’s not my first time at the rodeo, and I’ve reviewed a number of these types of Godly agreements for other clients before.

I can tell you firsthand that it is a frustrating endeavor, with one-sided, horribly termed agreements that don’t allow for much artist pushback. One is reminded of the clichéd phrase, “My way or the highway.” More often than not, proposed deals are sent as concrete, PDF agreements that have a pretty sure-fire way of communicating the “take it or leave it” attitude of these entities.

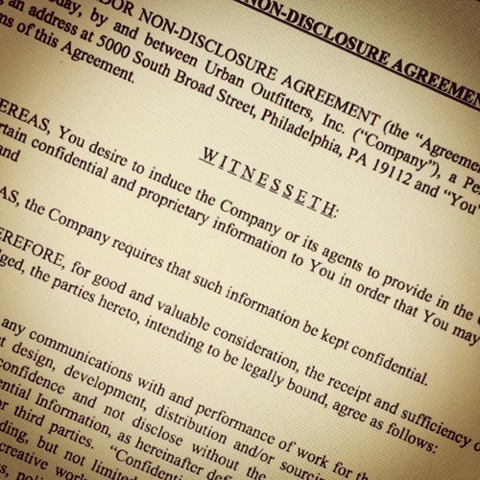

So back to my client. She had me take a look at Anthropologie’s “Vendor Non-Disclosure” agreement for her upcoming relationship with them. While reviewing the pretty typical confidentiality clauses in the agreement, I came across the following language:

“You (the Vendor), upon sale of product to the Company (Anthropologie), thereby assign to the Company any and all right, title and interest in the Vendor Designs, copyrights and intellectual property incorporated therein.”

Sorry, what?!? This is a simple confidentiality agreement in connection with vendors! For those not in the “know,” a vendor agreement is simply a supplier agreement, whereby (in the normal, non-Anthropologie world) an artist creates and manufactures a product and sends it to a distributor to sell via retail.

And a confidentiality agreement is an agreement to keep any trade secrets, know-how and company information to yourself. This is not a license agreement, this is not a collaboration agreement where the retail distributor is buying the rights to the designs.

So how does Anthropologie sneak this wholesale copyright transfer provision into the agreement, where the artist is giving away rights to their designs? In a standard Confidentiality/Non-Disclosure agreement that has nothing to do with intellectual property?

I’ll tell you how. Anthropologie and its kin are the hot quarterbacks from your high school days. You know, that guy who grew facial hair six months before every other male with a twinkle in his eye and perfectly mussed-up hair. He was drop-dead gorgeous, and he knew it. Well, that’s Anthropologie, and they know it. So, you, the artist, are a dime a dozen, and if you don’t want Anthro love, stand aside so the other drooling girls can get in line.

While Anthropologie and Williams-Sonoma do a great job fronting as altruistic businesses, collaborating away with the artistic community and recognizing the “true talent” in the room, the mess behind the scenes is daunting and one-sided, with license fees of 6%, if the artist is lucky.

So how do they get to continue screwing artists? Because artists let them. Many artists are (understandably) so excited for the opportunity and exposure that these companies lend that they don’t see the greedy intent to exploit. And they don’t feel that they have a choice. They either sign the agreement as is, or run the risk of becoming the nerdy girl sneaking back into the woodwork. It’s like high school never ends!

If we lived in a fair world, Anthropologie (and yes, I harp on them in particular) would be weighing the options of treating its artists with respect, or selling white, undecorated plates and unoriginal pillow lines. They would realize that it’s truly unfair to pay an artist 6% of sales (minus taxes, shipping, discounts, returns, blah blah blah) when the only thing they bring to the table is some quick, Chinese manufacturing and a blank canvas.

I vote that we at least acknowledge that the quarterback has got some acne and a bit of halitosis, instead of treating it like a God among men. I vote that artists start standing up for themselves, their beautiful artwork and the immense talent that they bring to this world, and demand fair treatment in their commercial dealings with these entities and similar bullies.

Once that happens, a whole new appreciation will have the opportunity to present itself. But until then, make sure you have an attorney review your deals with the devil.

except the article really answered no questions or gave any insights, other than “artist beware”–constructive help would have been more, well, helpful

Arlee, I think Emily has given the best possible advice in her final sentence:

“have an attorney review your deals with the devil”

and please note that this is Part One of her series. Look for more info in the next installment.

Agreed Carolyn – this topic isn’t the realm of DIY business tips for artists. I loved this article and just want to say: Amen.

I am always encouraging my creative friends (in whatever medium) to value their gifts and hard work enough not to “give it away” (literally and figuratively). Too many artists feel they * have* to, which only perpetuates the cycle of under appreciation for the real source of quality, worthwhile “content” we’ll call it. (Loved the spot on analogy of high school…)

Great article Emily – I look forward to more in your series!

Amen Emily! Wonderful article and wonderful heads-up.

Terrific article! Take a look at the Copyright Collaborative website- I am deeply impressed at Emily’s creation of a way to address these issues as a united front. Can’t wait to learn more.

Very timely article. Looking forward to part two. The trouble is, we artists need to eat and there are always younger, less well-informed and oh-so-eager new artists who will say “yes” if we don’t when these sorts of contracts come around. I’m really looking forward to hearing how to negotiate for better agreements when the deck seems so stacked against us – especially those of us who have been at their art long enough to be getting asked to the dance but who are not equal in power with the big companies that want our talent. I’ve stood up for better terms in contract negotiations only to be left with nothing after weeks or sometimes months of working with a company in the hopes of getting the deal. How to say “no” to certain terms but still get to “yes” for the deal – I really want to know how to do this because I keep getting shown the door when I stand up for myself and my work.

Great points, Sally. You are right that there are always other artists to take your place if you don’t agree to onerous terms. IMHO the best thing we can do is spread awareness and call out companies who are doing wrong by artists. Emily alludes to this in the article when she talks about companies promoting their partnership with artists to be “politically correct” – this is the result of pressure being brought to bear.

Hi Sally,

Were you personally negotiating contract points or did you have counsel batting for you? Representation can provide a valuable layer of separation that can help keep things strictly professional between the parties involved.

Nonetheless, congratulations in not being taken, even if the deal didn’t go through–let someone else get into a marginal situation.

Yes, thank you for a great part one. I look forwards to the articles to follow.

I think this article is really interesting because part of the problem is that everybody is always oh so polite and won’t name parties who wear their “we are the good ones” attitude as a mere construction. So if this kind of foul play is happening to a young inexperienced artist he will probably think this behavior must be standard and he shouldn’t ask too many question to be not immediately recognized as a newbie. When a big player is sending out a contract – how could he be wrong? Thank you so much for publishing this article.

Thanks everyone for your comments. I think it’s important to address the fact that there is an issue to begin with, and hopefully artists will start standing up for themselves in a group manner. Only then, I think, will the landscape change. But I think it’s very important to understand what you’re signing, and, with companies like Anthropologie, it’s hard to translate the legalese and to avoid the traps I mention above.

With some agreements, I think it is best to really consider what your “deal breakers” are and to address them first. And before you pay an attorney a lot of money to revise a one-sided agreement, be sure to approach the company to see if they’re amenable to changes in the agreement in the first place. If they’re not, and you’re not comfortable with certain terms, it may be time to walk away. When a door closes…

Do not for one minute think it isn’t happening elsewhere. Etsy , Places that offer to put your art on items they all have slipped in the anything you put on our pages is legally usable by them with NO COMPENSATION to the artist and they even claim copyright ownership in some of them. I read every website and when I see this I remove all content or do not join. I do not sell my artwork on Etsy only ooak jewelry that I make. My drawings,prints, paintings and sculptures will wait to be put on my own website for sale.

It’s a very slippery slope when dealing with licensing.. a European company I was in negotiations with had a clause in the contract that if my designs which I licensed to them showed up anywhere in the world, (even if I didn’t sell it to them – read “stolen”) I was liable for damages to the said European Company. Not only that, they would take me to court in Italy, in Italian where I would have to plead my case…

Did not go there.

Unbelievable … I’m glad you read the fine print on that contract!

If someone , ANYONE hands you a indecipherable contract and you don’t get or have a lawyer your not ready anyhow. Its hard not to get swept up in the moment of someone bigger than life wooing you and your work. Always step away before you agree to anything. By stepped away you’ve given yourself some space for quiet clarity. But yah, I think this article articulates as much as it could . Each circumstance is different. Its business- get a lawyer. Nuff said. With enough education under your belt you won’t make this mistake.

Thanks, Emily, for addressing this problem. Since the 1975 Copyright Act, this practice has been widely known as “work for hire.” As a magazine art director and illustrator at that time, I experienced first-hand the unfairness of work-for-hire contracts.

Suddenly, publishers began sneaking this term into their contracts with designers, photographers and illustrators. At first, we didn’t understand the ramifications. We soon realized, however, that by signing the contract we were giving up all of our rights to the artwork or design—and worse still, the right to make derivative artworks of the original concept. We fought back with pressure from our creative organizations such as the Society of Publication Designers, Society of Illustrators and the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA). Our best strategy, however, was to personally educate and negotiate with the publishers to whom we were selling our work. Ultimately, as in any negotiation, we had to be prepared to walk away if we could not get a fair deal—and we did.

In our negotiation with clients, we should try to transfer only limited rights to the client. It’s critical that the artist never transfers the right to make derivative works of the art. If you have a unique style or technique that defines your artwork and you transfer all rights for one piece of art to your client, it’s conceivable that the client could stop you from using that style or technique ever again. They could claim it’s derivative of the work that they now own. Also, they would have the right to hire other artists to use that technique or style on their behalf under the work-for-hire doctrine.

AIGA has a copyright guide that is very helpful: http://www.stopworkforhire.com/documents/aiga_6copyright_07.pdf. Of note is this statement: The client’s desire for work-for-hire or all rights is often for the purpose of preventing the client’s competitors from using the design or images in the design. The client can be protected against such competitive use by a simple clause in the contract stating: “The designer agrees not to license the design or any images contained therein to competitors of the client.” Another helpful link is http://www.stopworkforhire.com.

I think the Copyright Collaborative is a good idea. Anthropologie and other dictators only respect power. A single artist is not very powerful.

Hello all of those that wrote,

This was such a helpful and eye-opening thread and timely, as I am getting ready to contact companies I would like to license with. It’s currently September 7, 2020. I have a feeling there may be a glut of surface pattern designers, and I am one of them. Is there a good resource to read now, as I think this thread started in 2015.

Please advise and THANK YOU.

If the artists is being paid a royalty and does not actually produce the work, I think 6% is pretty good.

But I agree that slipping copyrights into a non disclosure agreement is inappropriate and the all encompassing copyright claims undeserved. The artist has a right to refuse and they should seriously consider doing so. If all copyrights are to be granted the company should be offering something of equitable value in return- beyond just a royalty on an unknown amount of business done. The artist should be able to establish terms such as a minimum payment in return for exclusivity.

I have been on the case of the New England Foundation for the Arts Terms of Agreement since 2007- they distribute grant money coming from taxpayers and in the process claim all rights every where for all eternity for anything that can be “deep linked” by being published in their date base- but of course the signer also has to agree never to deep link the NEFA site.

So they did nothing in response to protests until recently when they added a second terms of agreement on their website that looked more legit Until I compared the two contracts side by side and saw that it was down right devious. Here is my analysis :http://andersenstudiogallery.com/?p=168

Mackenzie, you hit the nail on the head in your analysis of internet terms of agreement and it dovetails with the point that Emily is making. Why do companies do it? Because they can (aided by their attorneys) and for the power it gives them over the artist (not to mention capturing the future profits that the artist would have received). As you noted, corporations and their attorneys know that an individual, like an artist, does not have the resources to hire their own attorney to fight such despicable contract terms.

How do we fight it? If all artists refused to do business with companies who conduct business this way—shame them and then just walk away from the negotiation—it would end the work-for-hire practice. Of course, companies know this won’t happen because we’re “starving” artists. However, I recommend a more aggressive action if you can’t get satisfaction through contract negotiation—file a lawsuit and encourage all other artists who are hurt by this practice to do the same. You don’t have to hire an attorney if you can’t afford one. You can represent yourself in court as the plaintiff. I’ve done it and won big money. I’m currently writing a book on how to be your own lawyer and win. Your goal is not to go to trial with your lawsuit, but to reach a negotiated settlement with the defendant company through the courts. The settlement that you ask for, rather than monetary, would be fair contract terms now and in the future. Once you’ve forced them into a lawsuit, you now have the advantage in the contract negotiation. Remember, as companies like to say in their contract negotiations, “it’s just business, nothing personal.” I recommend the book “Represent Yourself in Court” published by Nolo at http://www.nolo.com. Nolo publishes many do-it-yourself legal books, including trademark registration.

To James: I was doing the contract myself on the one in question. It was a small, local company so I felt able to do this having been licensing my work for over 25 years now. It was strange because I thought we were all set and then they tried to add a clause in which would retain all the copyrights and I informed them this was not what was in the original terms of the agreement. They countered with “oh we had our lawyer re-do the contract and they just put that in there.” It was sad because in our case the lawyer (theirs) actually caused the problem which we could not resolve. We had a good agreement till the lawyers stepped in. Which makes me wonder if the “evil” companies may not be fully responsible for this new arrogance in contract deals….perhaps it is the attorneys hired by the companies who are even further removed from the world of normal reality that are driving this upsurge of usury attitude.

I also got in trouble once because my agent sold the same copyrights to two different manufacturers. They did not take the blame for it either though they did try to explain how it happened (an error in re-titling the work) I was the one who had to make restitution to the second company because I was the owner of the copyrights and the signer of the contracts. I did seek legal council to try and fix the mess I was still out of luck.

I’m still confused about something in this article: it sounds like the article is saying that corporate retailers are trying to gain control of a vendor’s products copyrights when the vendor is the owner of those copyrights (which is an outrageous tactic! ). But then later in the article the discussion turns towards 6% licensing fees. Perhaps I’m missing something but these are two different issues, yes? In my experience, 6% for a licensing fee (assuming the rights are limited and non-exclusive) is an average fee for a product that is going to be manufactured and marketed by someone else. But if I manufacture the product and sell that product at wholesale, then usually that is a flat sale (no percentages) with no rights assigned. Are wholesale products now being sold to the retailer on a percentage basis? Could you please clarify?

Sally, the agreement Emily referred to was a “vendor agreement” which an artist might sign when wholesaling to a company. I think her point was that it is totally inappropriate to add licensing terms into that type of contract. It may be the case where you sell some of your work wholesale to them – then they own the copyright, and have the product made in China – then you don’t have a wholesale account anymore. They have in effect “stolen” your design through contractual terms, and even if they did pay you a royalty, it might be 6% instead of the wholesale cost.

How would I repost this great article link on my WordPress blog for other artists to see?

I currently have a contract with a project based art consulting firm that leaves the copyright with the artist. However, when I checked back with them I was informed their agent who signed me no longer works at the company. I emailed the new agent who emailed back rather succinctly that they’ll let me know if they have need for my work. Still no word so I am beginning to think they have no interest and are holding onto the 12-month contract for some reason. There is a 90-day written notice of contract termination request I can file but there’s language about liability for exclusives with other art consulting firms and “pending projects” (that I know nothing about?) etc. Maybe it’s time to have an attorney look at it.

Alice, Yes this definitely sounds like a good time to have an attorney review. You should be able to get out of a contract if the firm is not going to be placing your work. Good luck with this!

If you would like to repost the article, please only use the first few paragraphs on your blog with credit a link to the remainder of the article on ArtsyShark.

Thank you, Carolyn! I actually called them directly and received very good explanation which resolved the issue, positiviely. It takes a bit of courage to step out of comfort zones and glad I did.

I’ll post on my WordPress blog as per your instructions so that artists are aware of potential dangers. It’s always beneficial to be informed going into situations rather than having to fix the mess later. as your poster, Emily Danchuk mentions. Ms. Danchuk’s post gave me the courage to make the call.

Thank you so much for the useful information. I really appreciate it! I am looking forward to reading Part II. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you for calling out Anthropologie and other companies. Artists need to band together! I just had to deal with a situation where a client was trying to get all rights at a crazy cheap price. I’ve had so much experience with this that I was able to work it out amicably, but had I been new to the game, I might have caved.

A few years ago I was in the beginning stages of a licensing deal with Sesame Street. We had come to agreement on the terms, but when they sent me the contract, it was a “work for hire.” I pointed out to them that what we agreed upon was a licensing deal, not a buyout. My contact at Sesame Street said “Just sign this now, and we will sort it all out later. We need the art now.” of course, I said no way was I going to sign a contract that contradicted our agreement! The deal fell through, but I was shocked at how they tried to pull a fast one on me.

Education is where it’s at – we all need to SHARE our experiences and spread the word on the companies that want to trick artists into giving up their livelihood.

Thanks!

Good for you Maria for being a smart artist and not falling into such a sneaky trap! There is a feeling of empowerment when one has to say NO to a big brand like you did. I had a very similar situation with National Geographic many years ago. I had licensed a very successful puzzle image with a well-known puzzle company which NG carried in their catalog. The concept was mine and no one else was doing it at the time. NG wanted me to make a new puzzle just for them using the same concept but for a flat fee (which was very small) plus they wanted to own all the rights. I knew enough to know it was a bad deal and tried to negotiate for better terms but they basically swung their weight around and said it was their way or no deal. I declined their “offer”. I felt like I had finally “arrived” as an artist by having to say NO to such a big client!

And, as I knew they would, they stole my concept, got an in-house artist to create their “own” product. I’m sure it was very successful for them. Sadly, this seems to be the nature of many businesses these days: cheat and steal if you can get away with it. I don’t regret my decision but seeing my concept stolen was something I knew would happen eventually… and it has been now by many others as well, NG was just the first. It takes nerve to say no to these big clients and it may feel like a loss at the time, but it is ultimately a big gain because it is the right thing to do.

I haven’t done any licensing work yet, but I am thinking it would be nice if it was the other way around; we, the artists, would be the ones who provide the contract for the company to sign.

Agree!

Thank you so much. I am new trying to enter the market. I had fear that companies might use trick to take away my beautiful work. I know that for money or not, I am darn happy with my work. Reading this gave me extra confidence on how I can defend my work well.

The line after the quoted text is as follows:

” however, upon the sale by Vendor of “market goods” to Company, Vendor retains its intellectual property rights therein. ”

What are market goods?

thanks very much

E

This also applies to the apparel field. When my daughter was attending FIDM (SF) the school did a collaboration with Betabrand Crowdfunding. Each student was to design two outfits to be placed up for Crowdfunding. The outfits that were supported for crowdfunding went into manufacturing. They altered the dress a little making the skirt a little longer, however, concept and design were her ideas. I told her we needed to get a copyright or patent on the design. She told me in the industry it’s virtually impossible. Initially, they paid her royalty’s from sales. Although, it was a battle every quarter for her to be paid. It was always a huge deal. Typically the response was “check is in the mail.” Eventually, they dropped her name, claimed it as there own, and kept the profits. Bottom line she is an artist who was screwed. She was 22 years old at the time. Betabrand kept pestering her to design other items for them but because of the problems, she was having to get paid she didn’t. This the only thing I can find now on the internet about the dress. “The 360° Reversible Dress was the very first crowdfunding project from Think Tank designer Elizabeth Irwin, and it was such a hit, we’re now making it in two new colors: teal and gray, along with original black. Get a 360° Reversible Dress, and you’re really getting four dresses in one. Turn it inside out and go from a solid color to geometric …” Betabrand even admits it was a hit. Needless to say, she is always afraid to submit her ideas to any company. She was in Hollywood now as a Costume Designer and is doing very well.

Very interesting story, with a definite lesson involved. Thank you for sharing this, Adrienne. Taking a case like this to court is expensive and time-consuming. I’m glad your daughter is doing well, although she should have been paid!